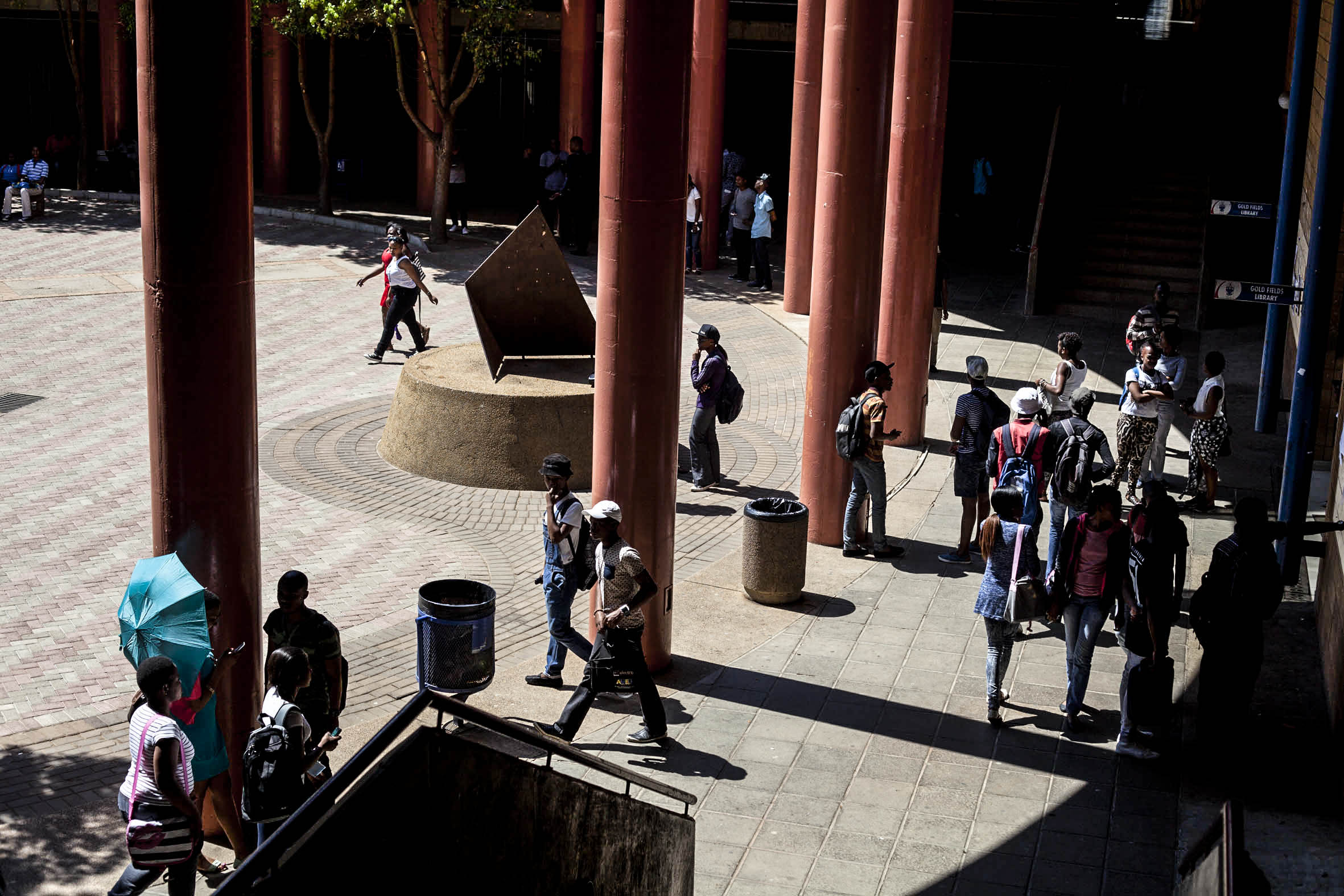

Young people have a desire for collective and meaningful ways to think together about a problem

This is a response to what we read as an unsubstantiated train of thought riddled with parochialism and condescension. Professor Rafael Winkler recently wrote an article entitled “Gen Z needs to get out of its comfort zone” (Mail & Guardian, 4 February 2025).

In the form of a love letter to the students we teach, we call on Winkler and readers to partake in the uncomfortable task of trying to better understand what our students seem to be communicating to us and how we can approach them more charitably.

His article is poised as an explanation of the tendencies of “left-leaning Gen Zs” and what he argues is their role in the decay of democracy.

As left-leaning young people who work in and study philosophy at various South African universities, we seem to be the target of Winkler’s article. In light of this, we thought to offer a response to what we read as an inflammatory and unsubstantiated train of thought riddled with parochialism and condescension.

Winkler centres his argument on a group we might call “Gen Z”, those born roughly between 1997 and 2012. He narrows it down by suggesting that he is interested in members of this generation who are left-leaning and who attend universities as students. He writes about this (relatively small group in society) as indicative of left-wing politics. This mode of analysis is flawed because it generalises about a larger heterogenous group of young people and left-leaning individuals from observations of a particular group of left-leaning students at universities.

In an attempt for a nuanced consideration, we will discuss Winkler’s claims as a reading of what seems to be the prevailing attitude among young people who are on the left, as indicated by the students we encounter in lecture halls. Rather than making sweeping claims, we will reflect on general tendencies we note in our experiences with and as part of this group. We do this with the goal of harnessing the potential which we believe makes itself evident in our lecture halls and to approach not only students, but young people in general with a sense of love.

On the importance of power

Winkler’s claims are guided toward the same major point: he wants to explain the decay of democracy as a result of the “Gen Z” political left’s anti-democratic insistence on remaining in their “comfort zones”. He describes the generation as being “fragile in body and mind”. He cites the usage of social media as a cause of this, suggesting that it has not made the generation tough enough to withstand critique. Additionally, he misunderstands the study of intersectionality as a blunt interpretive tool to tell who is evil in society and who is good.

In all of these points, Winkler’s comments (insults aside) seem to ignore the importance of something at play in all of the justifications he offers — power. It seems amiss to ignore the sheer extent to which young people have become fluent in the language of describing their world in terms of power relations.

Intersectionality is an example of a philosophy that enables these young people to think fluently about power relations and how these relations render some populations more vulnerable than others. Particularly, intersectional analyses arise from the oppressions that black women face, which are obscured by mainstream feminist and anti-racist movements. This analysis is indispensable in the South African context of gender-based violence, for example.

Winkler’s examples and arguments all show a recognition of young people’s concern with power, but he misunderstands it as a will to safety through ignorance. He describes Gen Z as a generation of cancel culture, one which openly expresses feelings about experiences of injustices, a generation which considers and shares thoughts about sexuality.

While these things seem to be true, Winkler gets wrong why these are the case. He claims that cancel culture is rooted in an individualistic desire to be safe from disagreement, and that Gen Z’s obsession with talking about sexual identity is a form of self-indulgence. Winkler additionally claims that sexual identity has not been a relevant political issue since the two generations which have come before Gen Z.

His explanation ignores that queer culture, cancel culture and racial solidarity hinge on the fact that the personal is political. These moves also pursue a path of collective thought and action. Importance is placed on power and wresting power from the hands of anyone who does not have the interests of the people in mind. These movements are imperfect in a range of ways, but they are about power.

Cancel culture, whether we agree with its efficacy, is an attempt to activate the wheels of justice. It is the recognition that through participation in a group, individuals can wield power against those who commit injustices to the end of accountability.

Furthermore, to suggest that sexual identity is now politically irrelevant is patently untrue. This is an idea that can only stem from a place of ignorance or privilege. In our own country, we have just seen the murder of the world’s first openly gay imam, Muhsin Hendricks. With suspicion that his murder was on account of his sexuality, this story lets us know that sexuality remains a rife political issue.

To speak about identity, whether in reference to queerness, race, gender, class or creed, is to think with others about subjectivity. This act is about understanding who we are in the world, and how we are produced and regarded in this world, an engagement that cannot be had without reference to power.

On comfort

With the idea of power in mind, we would like to address the notion that “Gen Z” is fragile and seeks comfort. In a context of racism, gender-based violence, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, the hoarding of wealth by the elite class and the pursuit of politics by this same elite — what comfort? Furthermore, should we blame anyone for seeking some sense of comfort in such a context?

If the young people to whom Winkler refers seek out ways to comprehend the objective reality which informs their everyday lives and their futures, that is not done to remain in a comfort zone. Instead, we might understand this as a desire to learn, guided by principled thought, and yes, guided by feelings in response to injustices which seek to dehumanise. The comfort they seek is collective comfort, not for deeming those in power evil, but in sharing the interest in accountability, a deeply democratic value.

What Winkler understands as a resistance to critical engagement, we would do well to understand as the impetus for fervent political engagement, and as a desire to expand knowledge insofar as it is driven by principle. Justice, fairness, redress, accountability and responsibility are things which seem to come up in our lecture halls. As teachers at the university, this is something we can work with.

If we choose to understand democracy as consensus-seeking, as Winkler does, we must make room for the possibility that there will be some ideas that are not worth negotiating about. For example, we might not want to pursue consensus-seeking with those who think it is worth debating about basic human rights and the principles of equality, justice and fairness. This is not anti-democratic; it is simply principled.

On love

When we begin to see things in this way, we see young people who have a desire for collective and meaningful ways to think together about a problem. Such an engagement depends on a shift from seeing our students as annoyances to loving them, a mode which allows for their potential to be revealed. The desire for collective thought demonstrated in the classroom shows that our students have no use for a notion of philosophy which depends on combat for its own sake, it should do something for us.

If there are any shared characteristics, it would be more apt to suggest that our students (and perhaps young people on the left) care about power and care about taking it back for principled ends. This has never been a comfortable task for those who have done it. As a youth strong in both body and mind, we are ready to pursue this task, in the classroom and outside of it, bound together by a sense of justice.

Kiasha Naidoo is an associate lecturer in philosophy at the University of the Western Cape and a doctoral candidate at Stellenbosch University. Tamlyn February is a lecturer in philosophy and doctoral student at Stellenbosch University. Nine-Marie van Veijeren is a doctoral student and a student worker in the philosophy department at Stellenbosch University.

Crédito: Link de origem

Comments are closed.