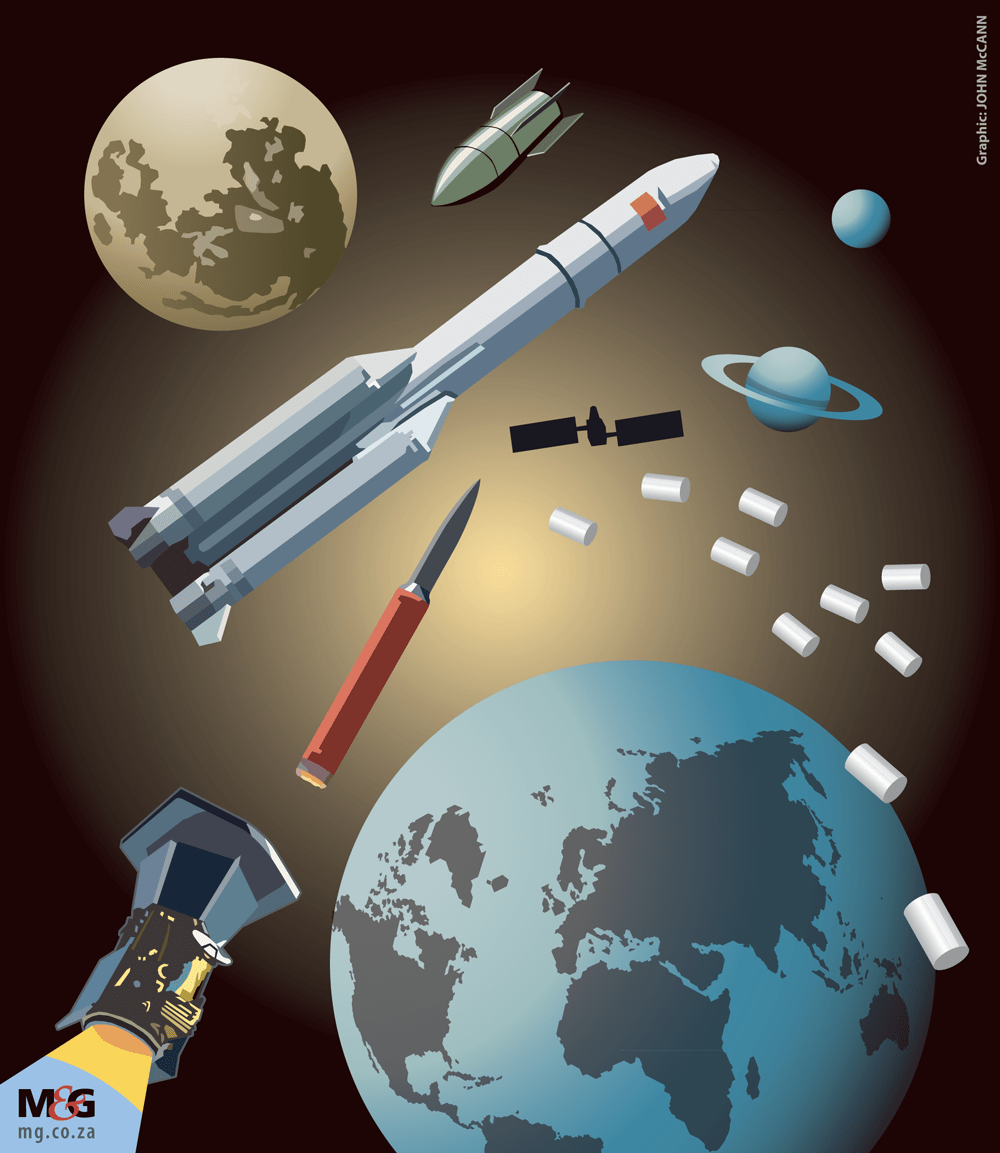

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

During the afternoon of 30 December last year, residents of Mukuku village in Makueni County, Kenya, were alarmed by a sudden loud crash.

“In the middle of a field lay a mysterious, smouldering metal ring, 2.5m across and weighing nearly 500kg,” academics Richard Ocaya and Thembinkosi Malevu wrote in the journal, Nature.

“Elsewhere, in western Uganda in May 2023, villagers reported seeing streaks of fire in the sky before debris rained down, scattering wreckage across a 40km-wide area.”

Ocaya is an associate professor in the department of physics at the University of the Free State and Malevu is a distinguished associate professor in the department of physics in the North-West University.

These were no ordinary meteorites, they said. “Across the world, from Texas to Saudi Arabia, from Cape Town to the Amazon rainforest, objects launched into low Earth orbit (LEO) are now falling back to Earth.”

Some burn up in the atmosphere, but others, especially those made of titanium and heat-resistant space-age alloys, survive re-entry and “slam into the ground”.

With thousands of satellites launched every year, the growing danger of space debris, particularly defunct satellites and spent rocket stages returning to Earth, can “potentially be catastrophic”.

“People everywhere on the planet, flying in aeroplanes, as well as in space, are increasingly at risk,” Ocaya and Malevu wrote, warning that the growing amount of space junk has become an immediate danger, necessitating space-traffic management and collision-avoidance strategies.

When people think about space law, they imagine something remote or relevant — rules written during the Cold War that are meant for superpowers, said Ocaya.

“But the reality is far more pressing. The space above our heads is getting dangerously crowded and the fallout literally is starting to reach the ground.”

He said the problem of space debris isn’t a hypothetical one. “It’s already landed here in multiple provinces across South Africa and many countries across the continent.”

For instance, in April 2000 in the Western Cape, one of the earliest recorded incidents involved three separate pieces of space debris. These objects came down near densely populated areas and critical infrastructure. While there were no injuries, it was a wake-up call, he said.

“In other words, we’re really not protected by geography and the demarcations we know as national borders become irrelevant to the problem of space debris.”

The researchers noted that since the beginning of the space age in 1957, humans have launched more than 17 000 satellites. In 2023, 212 successful launches from the International Space Station resulted in about 2 900 new satellites being placed in Earth’s orbit or beyond.

“These launches resulted in the addition of 377 rocket bodies and objects categorised as ‘debris’ to the orbital population.”

In the same year, the re-entry of 1 982 space objects was recorded; 678 were satellites, 96 were rocket stages and 1 208 were debris, said the researchers, citing a special report of the Inter-Agency Meeting on Outer Space Activities on developments in the United Nations system related to space debris.

“Imagine a large satellite, weighing several tonnes, re-entering Earth’s atmosphere without warning. Unlike the controlled descent of the Mir space station in 2001, this object might well veer off course and crash into a city. The devastation would be catastrophic, bringing legal, political and financial chaos.”

Ocaya and Malevu are developing a Cloud computing application for the prediction of the paths re-entering orbital debris and their likely landing zones on Earth.

Addressing this problem requires an approach that integrates tracking, accountability, debris removal and sustainability.

Spacefaring nations, private enterprises and international regulatory bodies must work together to enforce stringent policies, invest in innovative solutions and promote shared responsibility. “Accountability must become a cornerstone of space governance,” the researchers said.

Clearer international regulations and strong frameworks for dealing with space debris-related damage are needed. “Private operators must be held responsible for the debris they generate.”

They said satellites should be designed using materials that disintegrate on re-entry, preventing debris from surviving atmospheric burn-up and reaching Earth’s surface. “The goal should be not just to clear up space but to also do so in a way that does not create further ecological consequences.”

Without decisive action, Earth’s orbital environment could become so perilous that future exploration and commercial activity would be severely restricted.

Ocaya referred to the car-sized asteroid that struck the Eastern Cape in August.

“The problem of falling debris is quite similar when it happens,” he said. “The asteroid event revealed just how vulnerable rural communities are to these skyborne hazards.”

In June 2022, residents in Gauteng witnessed what appeared to be a fiery object breaking up overhead. This was identified as remnants from a Russian rocket that was used for a mission to the International Space Station.

“Although this particular object did not reach the ground, the visual impact highlighted just how space activity can affect public perception and safety. As recently as January this year, flights were delayed that were linked to issues surrounding space debris when SpaceX debris fell over the southern Indian Ocean — up to six hours of delays for flights connecting Johannesburg and Perth.”

The researchers cited a report by the United Nations University last year, which identified space debris among six interconnected risk tipping points that threaten the environment and human security.

The report noted that out of 34 260 objects tracked in orbit today, only about 25% are working satellites.

“Additionally, there are likely around 130 million pieces of debris too small to be tracked, measuring between 1mm and 1cm,” according to the report.

“Given that space debris travels at more than 25 000km an hour, even the smallest piece can cause significant damage if it collides with something, creating even more debris,” the report said.

Ocaya and Malevu said that the LEO, the region of space stretching from 160km to 2 000km above Earth’s surface, is the most congested orbital zone, home to imaging satellites, weather and communications constellations and space stations such as the International Space Station.

“It is also the most debris-laden part of space, harbouring more than 6 000 tonnes of human-made objects,” they said.

Because most satellite re-entries are uncontrolled, the problem of defunct satellites and spent rocket stages falling to Earth is being worsened. “Some space agencies deliberately steer defunct satellites into the ocean,” Oaya and Malevu said. “But many operators simply leave them to decay naturally, with no certainty about where they will land.”

Any location on Earth could be in the firing line. “As objects in LEO experience atmospheric drag, they gradually slow down and spiral back to Earth. Smaller fragments burn up during re-entry, but larger pieces — rocket stages, fuel tanks and satellite components — often survive, crashing to Earth at speeds of hundreds of kilometres per second.”

The energy released by their impacts can be equivalent to that of a small missile. The higher the re-entry speed, the further debris can spread.

“Predicting crash sites is extremely difficult. When an object falls from space, its path to Earth isn’t a straight line or even smooth. Predicting where it will land involves complex calculations and many factors, including Earth’s rotation, gravity, winds and the object’s initial speed and altitude.”

A major — and rarely discussed — concern is a potential collision between a falling piece of debris and commercial aircraft. At any given time, more than 10 000 aeroplanes are in the air worldwide, Ocaya said.

“There’s no telling just what the toll to human lives would be when a collision happens with such a falling object. These objects aren’t isolated; the incidents aren’t isolated and we are rather found wanting because aviation authorities are not able to predict where these objects will fall so people in the air are faced with a new hazard.”

He said South Africa is presently a “bystander” in the space race. “Although we have a fledgling space programme through various space-related activities such as the Square Kilometre Array, for instance, we are still a few decades back compared to major powers such as the United States, China and so on.”

But there is a growing private space sector in the country, which places South Africa in a unique position to start contributing to the solution.

“The vastness of our rural areas makes detecting and reporting fallen debris really quite challenging,” Ocaya said. “But perchance, when damage is eventually experienced, people will report these incidents. At the same time, we have a growing amount of space assets that it’s in our interests to protect from orbital collisions and uncontrolled re-entry.”

Clearly, that more people are witnessing more fireballs and experiencing disrupted flights means it’s a problem increasingly moving to the mainstream.

“Until that moment in time when people lose their lives directly, many will continue to think it’s someone else’s problem. No, it’s a real problem that we really need to contend with as early as possible before a catastrophe, a disaster, happens,” Ocaya stressed.

South Africa, being on the receiving end of space junk, can push for more modernised space law, which addresses not only satellites in orbit but space junk. “Countries can participate actively in ensure that … falling debris is regulated.”

Crédito: Link de origem