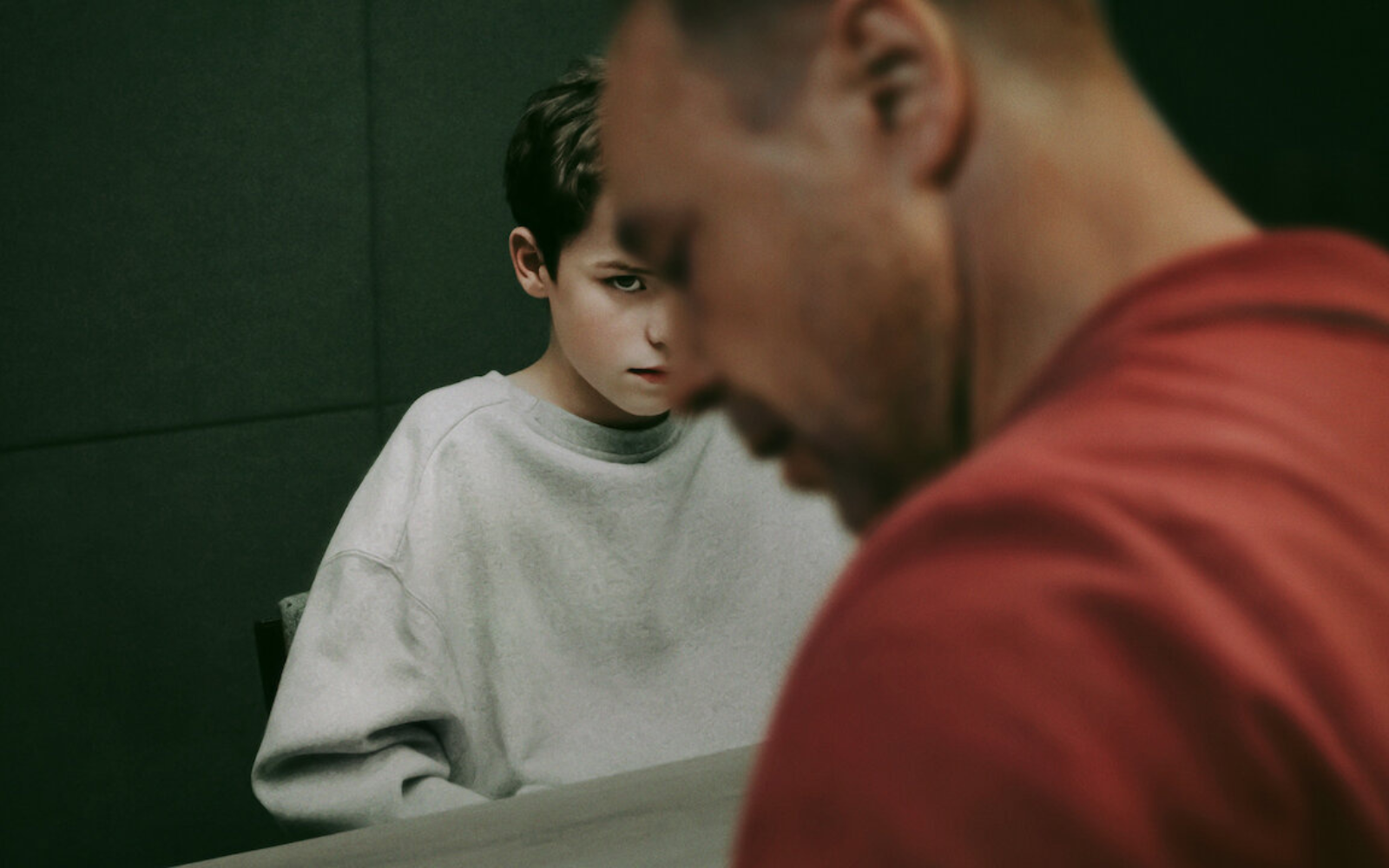

In the Netflix series Adolescence, we have no idea why Jamie Miller (Owen Cooper) is arrested at the beginning of the first episode. The tension from seeing a helpless 13-year-old boy escorted to a police station and interrogated holds us to the screen. Every minute of the one-hour episode, shot in a single continuous take, makes us feel like we are in the police station with the Miller family, viewing things through his parents’ disorientation.

As the plot unfolds, we are given clues to explain the inexplicable, but we can’t fully appreciate the show’s magnitude until the very last scene, a dramatic moment where we see the boy’s father (Stephen Graham) cry over his son’s teddy bear while asking it for forgiveness.

From an educational psychology angle, the show is ripe for analysis. One could comment on the premature sexualization of young girls and boys or the obsolete sense, for parents, that they can assume kids are safe when they’re at home in their rooms.

However, as a doctoral student in educational psychology, I am mostly concerned with human learning — both the cognitive development that must accompany successful learners, and how children and youth understand the world through relationships.

The state of Jamie’s cognitive development and of teenagers in general may help us understand his frame of mind — or the “why” that detective Luke Bascombe (Ashley Walters) pursues.

For parents, this show raises serious questions about the crisis in parent-child communication and how the internet is shaping children’s behaviour and minds. I suggest turning to the practice of dialogue as a way for parents to strengthen their communication with their children and learn about each other and the world.

Children’s minds

According to the government of Canada, “any human being below the age of 18” is defined as a child. Children can’t be recruited to join the Armed Forces, sign legal contracts, drive, vote, marry, drink alcohol and so on. As adults, we understand that these prohibitions not only protect them but also us.

Setting aside ethical reasons why children shouldn’t do any of these things, the major reason is due to the developmental state of their minds.

To better understand this, we must consider executive function, also called cognitive control. Executive function refers to the unconscious cognitive processes of abstract thinking, inhibition, impulse control and planning that allow us to consciously control and direct our thoughts to goals, actions and emotions.

Think of executive control as interconnected paths in the brain. In an adolescent’s brain, these paths resemble more of a labyrinth, with difficult and sometimes non-working passages.

Children and adolescents’ cognitive development are in “sensitive periods” in which their brains are more plastic and susceptible to environmental influences. Besides not having full control of their thought processes, research has also shown that abstract and more “neutral” cognitive skills develop earlier than those that involve motivated or emotionally charged actions.

Ability to weigh options still developing

Adolescents might be mature enough to solve complex math problems, but still feel helpless when needing to be polite to someone they believe offended them (not an easy task for adults either). In such a case, one would need to “step back” from the situation, and weigh options to respond.

An adult might think “maybe I misinterpreted what this person said” or “if I offend them back, I risk losing my job/friendship/reputation.” By dwelling on different course of actions, they don’t act impulsively.

This is precisely the ability that adolescents are still developing.

Virtual selves and threats

When adolescents engage with social media, they can be exposed to a threatening environment where they must assert their virtual selves and deal with bullying and inappropriate content, while lacking full control of their thought processes.

Yet, as American social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has chronicled, our society has allowed adolescents to take part in this at grave risk. With maturing cognitive capabilities, teens are at risk in an online environment that thrives on extreme views and hijacks emotions.

As a victim of cyberbullying, Jamie was probably not equipped with the cognitive abilities to step back from the situation and seek help. Instead, he responds to cruelty he experienced with cruelty he knew.

With unregulated internet use, in terms of both content and unrestricted time spent online, communication with parents atrophies. At its core, Adolescence is a painful wake-up call to the effects of unregulated internet usage in teens, and how the communication abyss that separates Gen X from Gen Z gives way to calamity.

Clueless adults, aware teens

Nowhere in the show is this distance more evident than when police detectives move cluelessly through Jamie’s school trying to understand his motives, while the students seem cynically aware of what really happened.

In a typical moment reflecting contemporary intergenerational dynamics in which the Gen Zs explain stuff to their analog parents, Bascombe’s son is the one to enlighten him about incel subculture and what certain emojis represent.

It becomes clear that pop-cultural references mean different things to a younger generation. For example, “red pill” was appropriated from The Matrix and is now used for those who “see the truth” and reject feminism.

Generations are comfortable communicating in different ways. Teens, for example, are clever texters. They use images, edit reels and create memes to convey subtle and often complex feelings.

In contrast, teens’ discomfort with face-to-face conversations is explicit in the last episode of Adolescence, when the Miller family drives to a hardware store. The parents play a song from their prom and reminisce. The oldest daughter is with them, but not present, focused on her phone and only sporadically joining the conversation.

Why dialogue matters

Parents and their children may find direction through dialogue. This ancient practice is based on the view of the world as becoming, with infinite internal and external contradictions that must be overcome so that new understandings of reality may emerge.

Dialogue was famously advanced as an educational practice by philosopher of education, Paulo Freire.

Freire believed people must come together to share their meanings of the world, and through this push and pull of ideas, reasons and opinions, conceptualize new forms of understanding. For parents, this means that without trying to understand what teens are saying and, importantly, how they are saying it, we can’t possibly create a better future for all of us.

Read More: About time: Netflix finally supports HDR10+ streaming

Open channel needed

Engaging in dialogue involves two things: asking and answering questions. It is not a matter of merely extracting information (although knowing what children are doing is important), but rather of mutually sharing interests and letting it guide discovery.

When parents and children find a channel, communication opens and for as long as the mutual interest is there, they can steadily build meaningful connections that transform how they see the world and their relationships.

With renewed urgency, dialogue that validates the interests and knowledge of both parents and children can offer a way out of the polarization created between them by long hours spent online.

Crédito: Link de origem