The God Edition | Dumpsite to sanctuary: The sacred mountain of Mamelodi restored – The Mail & Guardian

A mountain overlooking Mamelodi. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

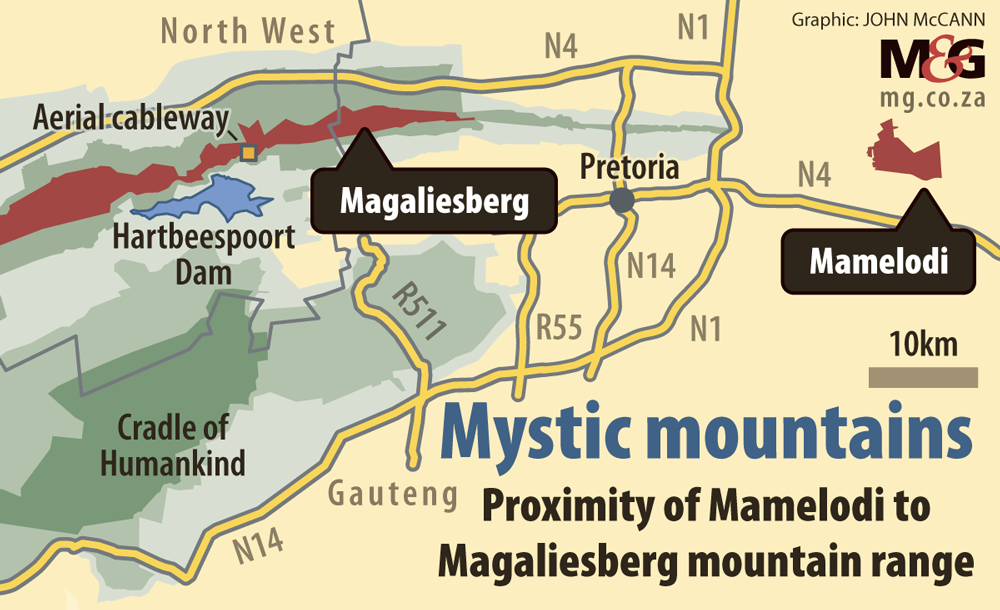

When a desecrated portion of the ancient Magaliesberg mountain that rises above the township of Mamelodi was weeping, Ephraim Cebisa Mabena heard its cries.

That was 24 years ago and the traditional health practitioner has spent his days since working to restore and heal the mountain, which had become a killing and dumping ground.

After all, it is the mountain that serves as the “shoulders of Mamelodi” where “you can see the tears of joy and of sorrow of Mamelodians”, he said.

Guided by the instructions of his ancestral spirits, Mabena was directed to a notorious piece of land on the mountain, west of Mamelodi.

“I saw the tears of the mountain for the first time in 2001,” said the lean and wiry 66-year-old, his neck adorned with traditional beads, who was wearing jeans ripped with holes, a testament to his laborious work.

“… Out of thousands of Mamelodians, I was the one who could see the tears of this mountain. I’m the only person who wore his boots and came to the mountain and said: ‘I am sorry’.”

During the 1970s and 1980s, the mountain had served as a hideout for political activists, like Mabena, a former operative of the ANC’s military wing Umkhonto weSizwe, who were on the run from the apartheid authorities.

It later turned into a place of torture when the security police started to use it as an interrogation site for captured activists. The panoramic view of Mamelodi that it provided further became an observation point for security forces to monitor activists and events in the township.

“As a young boy, I used to come to play hide and seek on the mountain, to collect some indigenous fruit or hunt a little bit but the most significant thing in my lifetime was after being beaten and interrogated by the police, they brought me here [to the mountain].

“…I was hiding myself here when the police were looking for me at home. Most of our comrades who stayed in Mamelodi, when they knew that the police were here, came on the mountain to hide themselves. Now we are so-called free, how many people have come back to say thank you to the mountain that we have survived.”

By the 1990s, it had turned into a blighted wasteland. Mabena had a series of dreams in which his grandfather directed him to rescue this piece of land, clean up the rubbish and to build a house of healing. “If you are a traditional doctor, you are guided by dreams and visions,” he said.

At first, he ignored the calling but the visions continued. Finally, in 2001 he founded the Mothong African Heritage Trust and began what appeared to be an unthinkable task: single-handedly turning the dumping site into an indigenous knowledge and heritage sanctuary.

“… I remember coming here and I said how can I build a house here. It didn’t make sense to me. What came at a particular time was how about let me clean this area and make a nice park. I realised later that I always believe what I think is not about myself, but this inner person inside me that is guiding me to the concept of building a park.”

Using rudimentary tools and hiring a few volunteers sporadically with his shoestring budget, Mabena cleared the land of the elements of crime and degradation, gradually transforming it into a nature conservation site of prized indigenous medicinal plants.

He planted grass and indigenous plants such as protea and mopani trees and rehabilitated a site gouged out by geologists into a bird sanctuary.

With the help of his wife, Mabel, who is also a traditional health practitioner, and their neighbour Mamorake Moila, it has become a peaceful botanical garden and heritage site where culturally valuable and important plants are cultivated and protected.

He faced down ridicule and derision from some members of the community. But as an endurance runner, the erstwhile founder of a local kickboxing and karate club, and of a medal-winning fencing club in Mamelodi, he stood his ground.

“A dumping area is foreign in a natural space,” Mabena said resolutely, as he stood on the slopes of the scenic mountain. “It’s a scar now and I am bandaging this scar … It’s like I’m healing this mountain … I cannot take this mountain to hospital but I must heal it by bringing my way of natural healing.

“It is un-African to leave such beautiful space to continuously become a dumping area so all my work is to apologise to nature. As Africans, we are not anti-environment, we are actually caretakers of the environment in the true sense of the word.”

He doesn’t know what the reasons are for the “scourge and the cancer of laziness today among our people”.

“This is a sign that our people must be awakened and begin to fold our sleeves and begin to work for our country and to bring back the image of our country – of our dams, of our rivers, and our forests.”

He utters another apology to the mountain. “I am saying, ‘sorry mountain, I know you have been providing a lot of traditional healers with a lot of plants but I came back to say thank you on behalf of my fellow traditional leaders. I know you are weeping and I know that the more we harvest some of these plants, the more some of these birds are flying away, the animals are going away, because there’s nothing more to eat.”

At his Ndebele-painted home, he showed his display of jars filled with different herbs, many gathered from plants harvested on the mountain that overlooks Section J in Mamelodi West where he lives and runs his practice, together with his wife.

Being a traditional healer is a “deeply entrenched gift” from the ancestors, he said. “This is my healing space … And at the end, I’ve developed this kind of mindset of saying I want to convert this place into an educational centre.

“One would remember that traditional healing has its own scars from apartheid. Our people were practicing under the Witchcraft [Suppression] Act. Now we are in a democratic dispensation, it must be a healing place but at same time, it must be a school of excellence for African indigenous knowledge systems.

“This is to educate our people that surely traditional healing has played such a significant role, where there were difficulties; where our people were performing under the Witchcraft Act … And I said no, let me convert this area into a school of excellence about ideas because everything that was done by our people, indigenously so, was somehow blacklisted.”

It serves as a museum, too, “that showcases the beauty of what our elders have done”, he said. “I want it to become a museum, it must become a school to show that our people never lack knowledge in terms of healing, in terms of food, in terms of doing things that can actually take a human being forward. Traditional healing has played such a significant role”.

He is not interested in criticising other people’s religions as long as it is uplifting people’s lives. “That’s the correct religion,” he said, firmly. “You teach me about your religion, I teach you about my religion – I believe in the ancestors – let’s come together and protect our country and protect our environment.”

He cited the example of black nursing students. “They still wonder what is traditional healing; what is traditional medicine all about because they are oriented with this Florence Nightingale belief system. If you count 10 students who are doing nursing, for six of them, their grandparents were traditional medicine practitioners.”

They had knowledge about medicinal plants. “But because history tells us that once you talk about indigenous knowledge, you talk about something that does not have scientific proof. Now when these students want to know, ‘Dr Mabena, how do you know this plant is poisonous or non-poisonous?’

“How did people know about those plants? They never went to school. That’s where my education starts because our people had enough time to study animals, to study biodiversity … They were able to study the environment because the mountains, the trees, the animals and the insects are our teachers.”

Traditional health practitioners are environmentalists, geologists and indigenous knowledge holders, who are central to conserving the environment, he said. They find the power to heal in nature.

He pointed to his display. “How do I know this is an indigenous Grandpa or Panado? It is because of my elder who had enough time to guide me with the support of the innermost. I am an aircraft but there is a pilot in me who is driving, who is navigating in me, using our indigenous software, which are our brains.”

For younger generations, life must never be a mirror where they only look upon themselves. “But it must be see-through glass, where you see me, I see you; each one, teach one … where we remember the elders who actually passed on this knowledge to us; it must be a baton.”

People distance themselves from nature, Mabel said. “I think everyone has his own reason why but I think it’s very important to be close to nature because the air that we breathe, we exchange with the trees and the flowers. Nature gives. And we must give back.”

Since its inception, Mothong has developed as a research site with several educational and research agencies investigating how indigenous plants can be processed into cosmetic and medicinal products.

Some of its backers include the departments of science and innovation, health and forestry, fisheries and environment as well as the University of Pretoria and Unisa, among others. The plan is ultimately to develop a processing plant on site.

As he walked through the indigenous medicinal nursery, where he cultivates plants used in his medicinal practice and also sells to other traditional healers, he singled out specific plants and elaborated on their healing properties.

Like animals, plants have secrets, he said. “It needs a well calculated traditional healer to understand the language that is spoken by different plants and different animals. Once you understand, you become a master of plants. You can be a botanist but if you don’t understand the deeper sense of each and every plant, you are just a botanist that has gone to school.”

It’s nearing the late afternoon and there’s more work to be done for Mabena and his team. “You will never see me in a suit,” he smiled. “I am 100% here all the time and I am not a pointing baas.”

The mountain is a natural asset for the people of Mamelodi, he said. “I wish of course it can get more exposure, more help, more input, more ideas, rather than people going outside of Mamelodi to the botanical gardens, when they have their own natural gardens right under their noses.”

He looked around at the mountain that he knows like the palm of his hand. “There are so many countless things why I say thank you Magalies. When I used to come and exercise and run up and down, wearing my boots, when I was a freedom fighter, when I was a young boy who came to hunt some birds and wild fruits.

“Today, I’m wearing my boots to say thank you Magalies, you were there when people wanted to perform their rituals. I can’t stop thanking this mountain for many reasons on behalf of our communities.

“When Martin Luther King said ‘I’ve been to the mountaintop’ for his reasons, he saw the glory of God. Then I’ve been to these mountaintops and I’ve been watching Mamelodi when it was crying during the apartheid times … These mountains are witnesses of so many things that are happening down there. Mountains have eyes.”

Crédito: Link de origem