The fishing boats were less than halfway to their destination — a ring of reefs and rocks known as Scarborough Shoal — when a Chinese coast guard ship appeared on the horizon. Those aboard the fishing boats, including Washington Post journalists, watched as the Chinese ship cut across the reflection of the setting sun. A second Chinese vessel arrived. Then a third. Before nightfall, the Philippine convoy was encircled.

The Philippines has been waging its most vigorous campaign yet to push back against China’s growing assertiveness in the South China Sea. After Ferdinand Marcos Jr. became president two years ago, he launched a campaign backed by the United States and other allies to resist China’s efforts at projecting military and political dominance over this strategic waterway, which is also claimed in part by six other governments.

But over the past year, the Philippine effort has also demonstrated the limits of its power. In China, the Philippines faces one of the world’s largest maritime forces, which has routinely rammed, swarmed and pounded Philippine vessels with water cannons. Manila’s drive to “establish a new status quo” in the South China Sea has been largely dismissed by Beijing, which has doubled down on its claims over the waterway, said Greg Poling, director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at the D.C.-based Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The Philippines claims dozens of disputed islands and maritime features such as reefs that fall within what it calls the West Philippine Sea, recently building military facilities on the contested Pag-Asa Island and deploying warships to another atoll called Sabina Shoal. Speaking at an international security conference in Singapore late last month, Marcos warned, “The lines we draw on our waters are derived not from imagination but from international law. I do not intend to yield. Filipinos do not yield.”

Nowhere in the South China Sea is the Philippine campaign — and its limits — clearer than at Scarborough Shoal, which Chinese warships seized in 2012. Scarborough sits 140 miles off the coast of the Philippines, well within what the country deems its 200-mile exclusive economic zone. But China says it has “indisputable sovereignty” over the shoal, which it calls Huangyan Dao. For a decade, Chinese ships have blocked Philippine fishermen from accessing its inner lagoon and chased away vessels that have drifted too close.

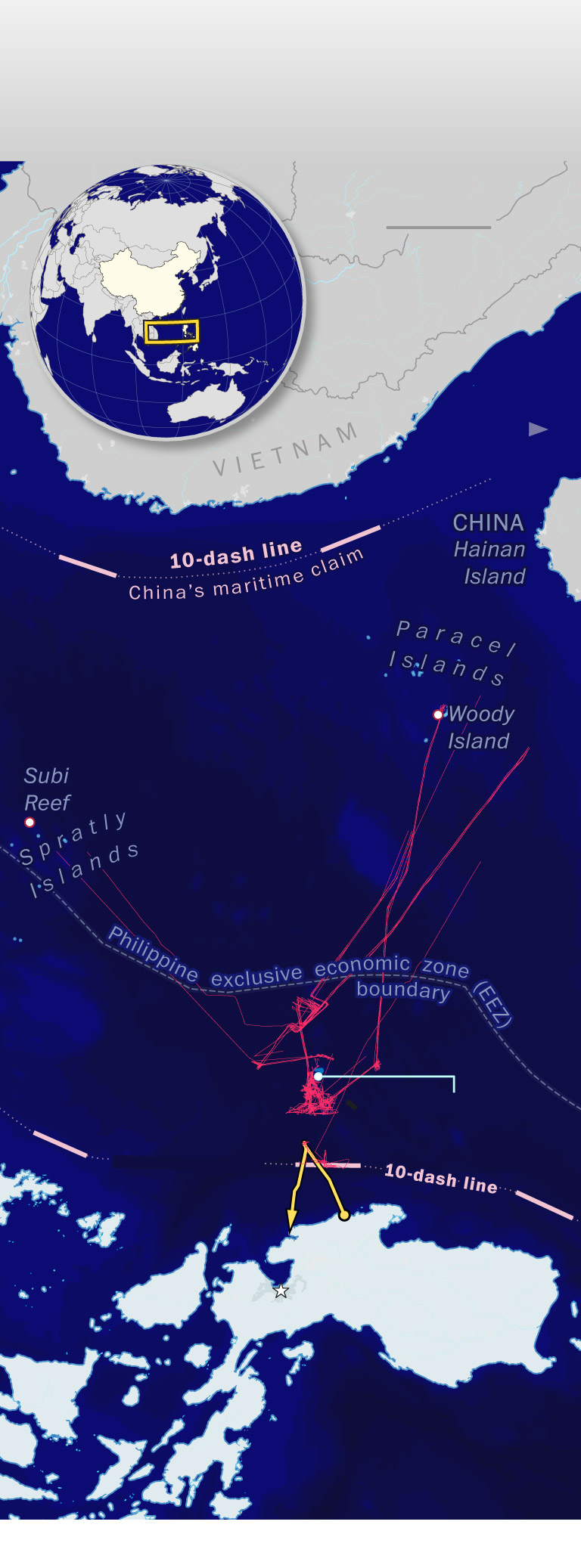

Ship traffic to Scarborough Shoal

Over the course of three days, China sent over

40 vessels to prevent a Philippine convoy of

fishing boats from reaching a shoal that

China has controlled since 2012.

China is able to launch vessels

from bases it maintains in the

Paracel and Spratly islands

as well as from the mainland.

The Philippine

convoy turned

around 50 miles

from the shoal.

Note: Some vessels had their trackers turned off or did not transmit location data during this incident.

Source: SeaLight at the Gordian Knot Center

for National Security Innovation at Stanford University

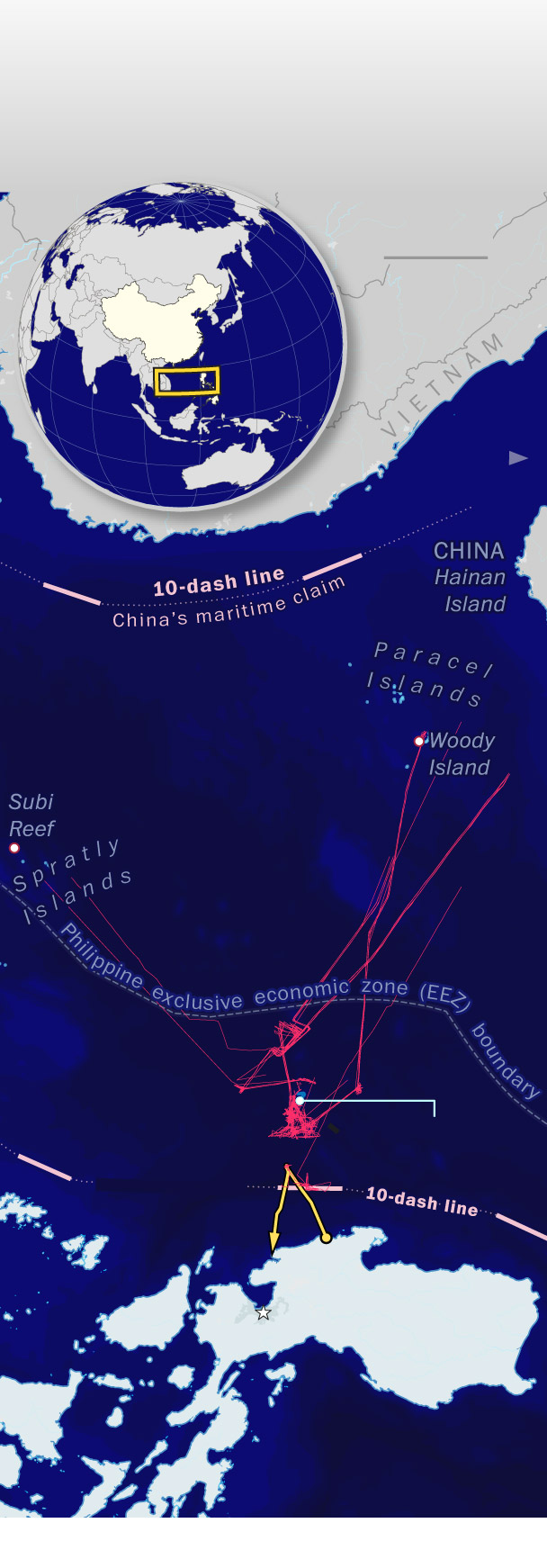

Ship traffic to Scarborough Shoal

Over the course of three days, China sent over 40 vessels

to prevent a Philippine convoy of fishing boats from

reaching a shoal that China has controlled since 2012.

China is able to launch vessels

from bases it maintains in the

Paracel and Spratly islands

as well as from the mainland.

The Philippine

convoy turned

around 50 miles

from the shoal.

Note: Some vessels had their trackers turned off or did not transmit location data during this incident between May 13-16.

Source: SeaLight at the Gordian Knot Center for National Security

Innovation at Stanford University

Ship traffic to Scarborough Shoal

Over the course of three days, China sent over 40

vessels to prevent a Philippine convoy of fishing boats

from reaching a shoal that China has controlled

since 2012.

China is able to launch vessels

from bases it maintains in the

Paracel and Spratly islands

as well as from the mainland.

The Philippine

convoy turned

around 50 miles

from the shoal.

Note: Some vessels had their trackers turned off or did not transmit location data during this incident between May 13-16.

Source: SeaLight at the Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation at Stanford University

Now, the Philippines is again pressing its claim to Scarborough. The Philippines is working with allies to ramp up surveillance of maritime activity, say Philippine navy officials. The Philippine coast guard and bureau of fisheries last year began regular patrols to the shoal. And last month, Philippine fishermen and activists undertook a privately organized mission to distribute supplies to other fishermen operating near Scarborough and, in doing so, assert the right of Philippine civilians to sail through these waters.

But hours before the flotilla departed May 15, aerial surveillance imagery and ship-tracking data showed scores of Chinese vessels cruising toward the shoal. Not since 2012 had there been such a show of force, said Ray Powell, an analyst at Stanford University’s Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation.

A few dozen Philippine fishermen dropped out from the voyage days before departure because of concerns their small boats would be wrecked by Chinese water cannons. But the bulk of the convoy decided to press on.

At a news conference after the Philippine flotilla had set sail, a spokesman for China’s Foreign Ministry, Wang Wenbin, said Beijing planned to defend its rights. “Relevant responsibilities and consequences,” he warned, “shall be borne solely by the Philippines.”

Scarborough had long been one of the most prized fishing grounds in the South China Sea, drawing boats from the Philippines, China, Vietnam and elsewhere. Older fishermen recall a sparkling blue lagoon with schools of fleshy mackerel tuna and coral reefs that hid a buffet of rockfish, needlefish and clams.

Over much of the past century, the Philippines laid claim to the shoal, occasionally expelling boats from other countries. The shoal served as a precious harbor for Philippine boats trying to make it home through storms and typhoons. Its proximity to Luzon, where the Philippine capital, Manila, is located, also made control over the shoal a matter of national security.

So it came not just as a shock but an embarrassment to the Philippines, say current and former officials, when, following a lengthy confrontation in 2012, the Chinese effectively took it for themselves. Trouble erupted when Philippine officials said one of their warships had caught Chinese fishermen at the shoal poaching rare animals and corals. After the Philippine navy intervened to stop the fishermen, China responded by dispatching two law enforcement vessels. The Philippines eventually withdrew its ships. But the Chinese remained.

It was a turning point in the South China Sea, said Renard Sexton, a political scientist at Emory University who studies conflict in Asia. Scarborough became a symbol of what could be gained and lost in an era of rising Chinese power. For Beijing, on the cusp of a massive military buildup at sea, it was a statement to the world that China would not back down.

After that, China stationed at least one coast guard ship at the mouth of the shoal at all times. Chinese maritime militia — government-funded ships used to establish China’s presence in disputed waters — shadowed Philippine fishing boats near the shoal and sometimes confiscated their catches. Revenue for fishermen who used to rely on Scarborough diminished so much that some quit fishing entirely, say union leaders.

In 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration, an international tribunal, ruled that China had no legal claim to the shoal and could not block Philippine boats from fishing there. But China dismissed the ruling. That same year, Rodrigo Duterte was elected president of the Philippines, pursuing warmer ties with China and muting claims in the South China Sea. Already underfunded, the Philippine navy and coast guard languished under Duterte, said Jose Antonio Custodio, a Philippine military historian.

China’s grip over Scarborough had tightened sharply, say Philippine and Western security analysts, when in 2022, the Philippines elected Marcos as president. At his first nationwide address, he made clear that the Philippines would not abandon “even one square inch of territory.”

Captain Jory Aguian, 38, coasted his boat, named the Paty, to a stop. It floated adrift, 90 miles from port, 50 miles shy of Scarborough.

Chinese coast guard ships had shadowed the flotilla of four Philippine boats overnight, along with a single Philippine coast guard vessel. The largest of the fishing boats was a mere 70 feet long, barely a fifth the length of the Chinese coast guard boats. Now, on board the Paty and the other fishing boats, a debate was unfolding over the radio about whether to proceed.

Inside his cabin, Aguian tapped the steering wheel anxiously. He wanted to sail on.

Aguian had never seen Scarborough. His father, a shipbuilder from the town of Subic, had told him how beautiful the shoal was. But by the time Aguian became a captain, most fishermen with midsize boats like his generally regarded it as a waste of fuel — and a hazard — to fish there, he said.

But fishermen whose boats were too small to sail far into the Pacific still consider Scarborough to be the richest fishing grounds within reach and, for nationalist reasons as well, have been reluctant to give it up. So when Aguian heard this expedition was being planned, he volunteered his boat and half his crew. He wanted to fight for the shoal.

Among the 21 people on his boat, feelings were mixed. Most of the crew, composed of fishermen in their 40s and 50s fed up with the Chinese, wanted to sail on. But a medic on board was hesitant. So was a college student who belonged to the activist group Atin Ito, which had organized the voyage. “Honestly,” said Matthew Silverio, 21, “I’m terrified.”

The Paty was the smallest of the four boats in the flotilla, a traditional Philippine outrigger only 40 feet long held together by wood, bamboo poles, rope and zip ties. If the Chinese deployed water cannons, the roof of the boat’s cabin would fly off, leaving the engine exposed, said crew members. For those on board, there’d be nowhere to hide.

Voices from the sea

Click to see and read more from fishermen and others who sail in the South China Sea.

And there was another consideration that only a handful on the flotilla knew about. A fifth fishing boat had earlier sailed ahead of the main flotilla and been confronted by a Chinese warship. As the boat tried to circumvent the navy vessel, a Philippine fisherman working at Scarborough Shoal sent back an urgent message, recounted Mark Figueras, an activist on board:

“Do not proceed! Do not proceed!”

Chinese ships had sailed upon the shoal in force and were chasing away every last Philippine boat, Figueras said. Even if the flotilla made it to the shoal, there’d be no one left there to receive supplies.

Slightly before 9 a.m., the radio in Aguian’s cabin crackled with a final verdict. The captain started up the engine. The boats were turning around.

The morning after returning to shore, organizers of the voyage celebrated it as a success. The Philippines had sent a convoy of wooden fishing boats into the West Philippine Sea, and China had responded with warships, said Rafaela David, a co-convener of the Atin Ito coalition. “It seems China is afraid,” said David.

Not everyone saw it that way. Figueras sighed and shook his head as he talked about the disappointment of altering course just 20 miles away from Scarborough. Many of the fishermen aboard the four boats, including Aguian and most of his crew, said that if it had been up to them, the flotilla would have pressed on.

The Philippines has “no teeth,” said Raul Bogs Patijdas, 58, a technician on Aguian’s boat.

“We should have gone straight to the shoal because it is ours,” said Jose Takoyan, 44, another crew member. Instead, he said, the Chinese “escorted” the Philippine boats out of their own waters. “I don’t know how China got so powerful but I know they prepared for war,” he said. “That’s what we didn’t do. We didn’t prepare for war.”

A week after the sail, ship tracking data showed at least eight Chinese vessels, including two coast guard ships, surrounding Scarborough. The Paty and the other boats were headed back out to sea to fish. But at least for now, Aguian said, none were going to Scarborough.

Regine Cabato contributed reporting from Zambales, Philippines. Map by Laris Karklis.

Credit: Source link